The Hero's Journey, The Heroine's Journey

Thinking about narrative structures and different frameworks to analyze stories

Chances are, you’re familiar with The Hero’s Journey; whether or not you recognize the term, on some level, this narrative arc is deeply engrained in your mind, and influences the way you understand stories. Even if you haven’t listened to our latest episode, in which we talk all about it, you might still recognize the hero’s journey in The Odyssey, Star Wars, or even Wonder Woman.

But when we talk about a “hero” we naturally think, too, of the “heroine.”

You are reading The Novel Tea Newsletter, companion to The Novel Tea Podcast, where you’ll find book reviews, thematic literary analysis, and cultural commentary to help you thoughtfully engage with the world.

New posts come out every Tuesday. If you enjoy reading our work, please consider subscribing and sharing the newsletter with others.

The Heroine’s Journey

In our latest podcast episode, we talk in depth about Joseph Campbell’s conceptualization of ‘The Hero’s Journey’ (most famously detailed in his book The Hero with a Thousand Faces). Since Campbell published his ideas, they have been adapted by many others - for example, Christopher Vogler, a Hollywood writer and producer, built on Campbell’s work in his book The Writer’s Journey: Mythic Structure for Writers.

So what about the heroine’s journey? Maureen Murdock, a Jungian psychotherapist, and once a student of Campbell, supposedly asked Campbell about the heroine’s journey, to get the response: “Women don’t need to make the journey.”

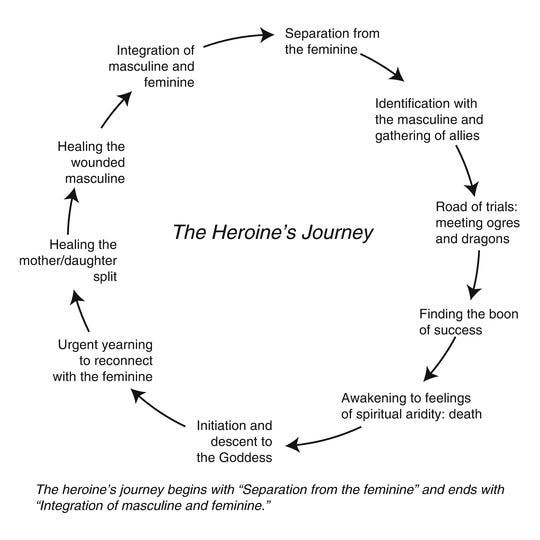

In response to this statement, and probably Campbell’s ideas in general, Murdock wrote the book The Heroine’s Journey: Woman’s Quest for Wholeness. Here is a visual representation of her concept:

I don’t really buy Murdoch’s model (though I definitely don’t have the training to analyze it in detail) - for one thing, it is too convoluted, involving all kinds of fusing and separating of the masculine and feminine. And more importantly, her book was never intended to describe narrative structure; it was written as a self-help book for women.

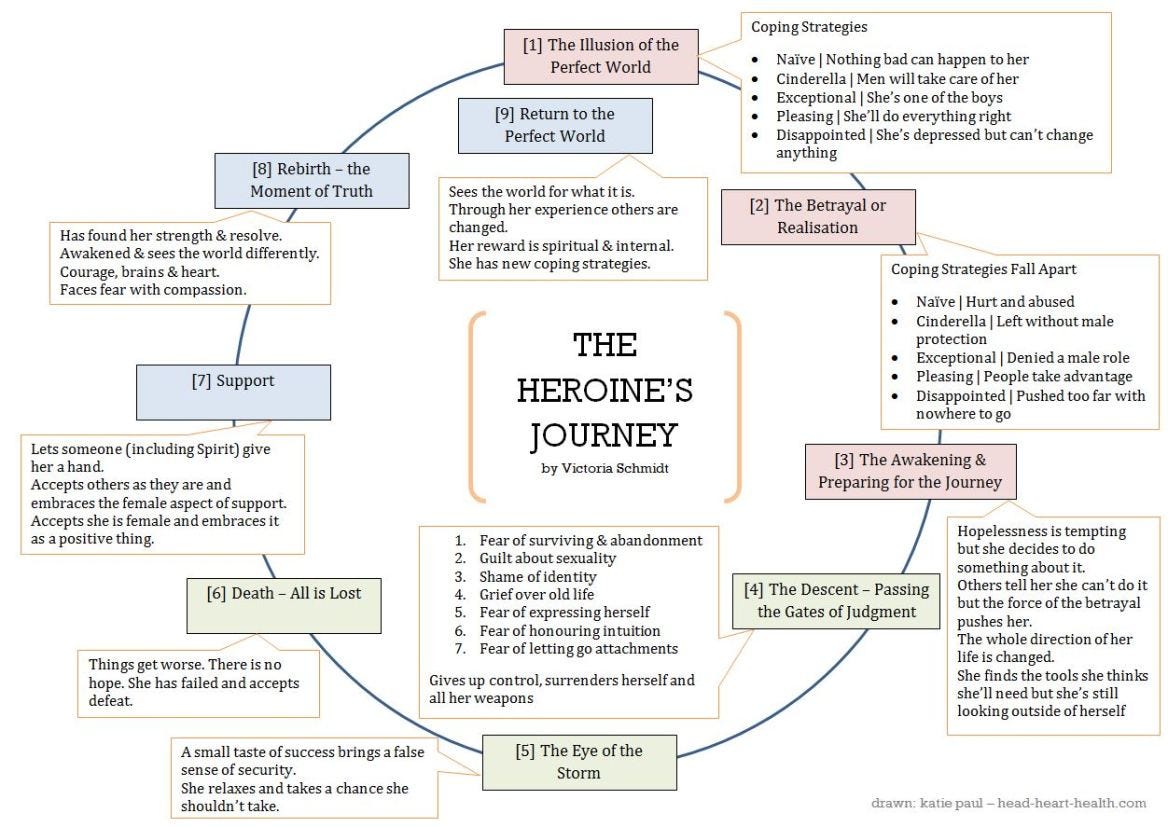

Victoria Lynn Schmidt, a screenwriter and author with a doctorate in psychology, later described the Feminine and Masculine Journeys in her book 45 Master Characters: Mythic Models for Creating Original Characters - I know it looks complicated, but stay with me, I promise all this research is heading somewhere.

And more recently, in 2021, Maria Tatar, a world-renowned folklorist, published The Heroine with 1001 Faces, in which she explores heroines in myths, folklore, and literature — including Shahrazade, Nancy Drew, Jane Eyre, and Wonder Woman. In preparing this newsletter, I read parts of it, but if you don’t have time to read the whole book, this NYT review provides a 1000-foot view of its concepts.1

After looking through all these sources, I was able to trace a few common themes that I think distinguish the heroine’s journey from the hero’s journey.

While the hero’s journey starts with a call to action, the heroine’s journey starts with loss or something being taken away. The story of The Beauty and the Beast starts out with our protagonist being separated from her family, and taken away to a cruel, inhospitable new environment. In Greek myth, too, Persephone is stolen, taken away from the earth, by Hades, into the underworld, and is thus deprived of her connection with the earth and her loved ones.

As Neha discussed on the podcast, the hero’s journey is one of adventure and conquering, whereas the heroine’s journey is one of exploration and discovery. Think of Pandora and Eve, in Greek and Christian mythology, whose stories begin with a desire for knowledge. Women in popular stories, from Jo March to Rory Gilmore, aspire to be writers - discoverers and chroniclers of the truth. And to revisit Belle, her journey, too, is one of discovery, not adventure and battle - over time she learns who the Beast truly is, and how to break the curse that has been cast over his castle.

The structure of the heroine’s journey is often circular rather than linear. Because I read it recently, I am thinking of To the Lighthouse by Virginia Woolf, and how its circular narration mirrors the journeys of Mrs. Ramsay and Lily Briscoe, the two female protagonists of the novel. Shahrazade, in A Thousand and One Nights, moves from day to night, and night to day, weaving stories to deceive the prince as she talks around and around in circles. Or think again of Persephone, who is fated to alternate between the Underworld and our world for the rest of her life, her journeys dictating the cyclical weather patterns that give us seasons.

I should also make the distinction that when talking about these journeys, the terms hero and heroine are not gender-specific. Historically, women have been confined to domestic spheres, with their scope of movement severely limited, resulting in a specific type of narrative journey. However, once storytelling moved from predominantly oral to the written format, characters’ journeys overall became more introspective - so while we don’t necessarily get much of Achilles’ inner thoughts from Homer’s Illiad, in Robinson Crusoe, we start to hear directly from the protagonist, in the form of letters and other written logs, about his experiences and reflections. And with women starting to gain more agency in the world in the past few centuries, their stories could also become ones of adventure. I think these changes helped to blur the gendered lines of ‘hero’ and ‘heroine.’

On the podcast, we discussed how Harry Potter actually undertakes a heroine’s journey, not a hero’s. And in the graphic I made below (which includes some spoilers), you’ll see that Katniss Everdeen of The Hunger Games undertakes a hero’s journey.

So hero and heroine really don’t have much to do with gender or biologic sex. I think it is easier to simplify it - the hero’s journey involves an exterior call to action; the heroine’s, an internal one.

In fact, let’s just go one step further, removing the construct of gender, to say this: in every strong narrative, the main character goes on a journey. Sometimes it is exterior, and sometimes it is interior. But often - in the most interesting stories - it is both.

If those three points are the supposed differences between hero/heroine, then there are no differences:

1. Call to action: Campbell already wrote that the adventure can start with a lose, so already there.

2. Conquer: not true. Campbell speaks not of conquering, but of an initiation ritual, so it actually included discovery and self-discovery.

3. Circularity: that was explicitly in Campbell's model. He even draw a circle for the hero's journey.

The basics of the hero's journey already included the structure of myths like Persephone's or Snow White's. In fact, I have used this last one in my classes to talk about Campbell's model. One of the strengths of Campbell's model is, precisely, its inclusiveness.

I can't wait to read the full post -- this is exciting! I'm so interested that Katniss takes a traditional hero's journey, while Harry takes a heroine's. Can't wait to check out your analysis!!