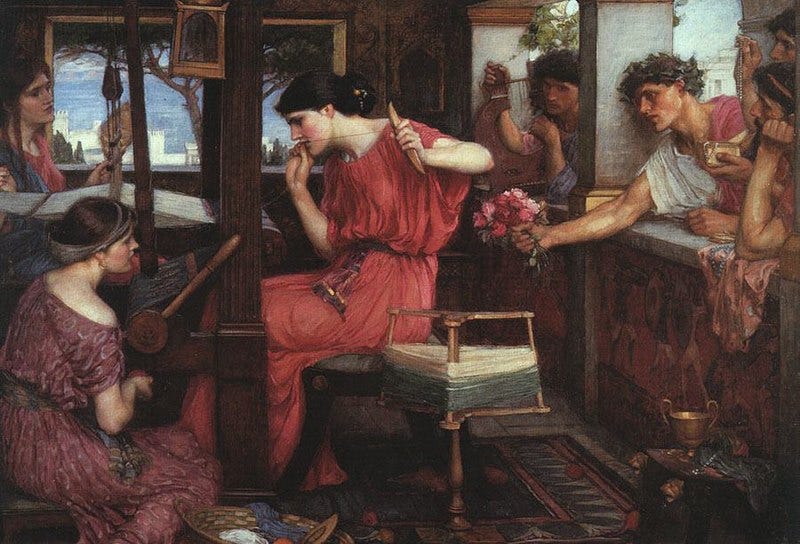

Last week on the podcast, Neha and I talked about The Penelopiad by Margaret Atwood, a retelling of The Odyssey that centers Penelope and the twelve hanged maids. At first, this seems like an odd choice for the only Atwood book we’ll be discussing this season. But even though Atwood may be best known for her science fiction and dystopian works, the common thread running throughout all her stories is one of myths, retellings, and reimagined stories.

In 1992, Atwood published a collection of short stories titled Good Bones, in which one of the stories, Gertrude Talks Balk (which you can find here), is in direct conversation with Shakespeare’s Hamlet. In the story, Gertrude talks directly to Hamlet, chastising him for his dirty laundry, explaining what she likes about Claudius, and finally sharing her own perspective on what really happened to the King (read a more in-depth analysis here).

What is striking in this story is the modern language that Atwood uses, dispensing with any pretenses, not even trying to imitate the tone and style of her source text. She takes this same tone in The Penelopiad, speaking directly to the reader in the 21st century, even when talking about events that may have occurred thousands of years ago.

In discussing some of these narrative choices on the podcast, we also talked about why she chose to tell the story in the form of a novel, alternating Penelope’s thoughts with poetic chorus lines.

In fact, two years after the book first came out, Atwood adapted the story for the stage - and I wonder why she didn’t write it this way to begin with, because I think that the maid’s laments are so powerful when they literally take center stage. Take a look, and tell us what you think:

You are reading The Novel Tea Newsletter, a companion to The Novel Tea podcast. Here, you’ll find book reviews, thematic literary analysis, and cultural commentary to help you thoughtfully engage with the world.

New posts come out every Tuesday. If you enjoy reading our work, and want to show your appreciation for the time and effort we put into it, please consider subscribing and sharing our newsletter with others.

A Poem in Which Helen of Troy is a Stripper

In our podcast discussion, we talked about Helen’s character in The Penelopiad - she was portrayed as catty, mean, and frankly, downright unlikeable (more on this next week). But Helen previously starred in Atwood’s works in a poem, Helen of Troy Does Countertop Dancing (which first appeared in the collection Morning in the Burned House, 1995). What is Helen like in this version?

You can read the full poem here, but I’d like to focus on the last stanza:

Not that anyone here

but you would understand.

The rest of them would like to watch me

and feel nothing. Reduce me to components

as in a clock factory or abattoir.

Crush out the mystery.

Wall me up alive

in my own body.

They'd like to see through me,

but nothing is more opaque

than absolute transparency.

Look--my feet don't hit the marble!

Like breath or a balloon, I'm rising,

I hover six inches in the air

in my blazing swan-egg of light.

You think I'm not a goddess?

Try me.

This is a torch song.

Touch me and you'll burn.

When the poem starts out, she asserts herself, daring other women to denigrate her for her choice of profession - but as it goes on into the second stanza, the façade starts to crumble and we see the toll it takes on her: “Speaking of which, it’s the smiling tires me out the most. This, and the pretence that I can’t hear them”

By the last stanza (above), we have reached her core - her essence, and her true self, which only certain people (maybe only one person? Who is the “you” in “anyone here but you would understand”?) can understand.

In the first few stanzas of the poem, there is a destructive force that we see beating down on her. But by the end, she shows us that she can’t be grabbed or held captive: “breath” “air” and “light” - all these elements are elusive, slippery, and intangible; they are natural things. They have power but cannot be weaponized.

Except - fire can be. Her last line: “Touch me and you’ll burn”

The Mythologic Handmaids and Their Tales

This theme of women being deprived of their agency and trying to regain power can be traced through many of Atwood’s works. In what is probably her most popular novel, The Handmaid’s Tale, the women of Gilead are assigned to the ruling class and forced to bear their children. This story feels particularly relevant in a post-Roe v. Wade world, but many of the ideas in this book can be traced back to Biblical mythology.

In the Old Testament, Jacob, after fleeing from his brother, arrives at his uncle Laban’s home, where he falls in love with his uncle’s daughter, Rachel. Jacob is tasked to work for Laban for seven years to gain Rachel’s hand in marriage, but when this time is up, he is wed to Rachel’s older sister, Leah, instead. When he eventually is allowed to marry Rachel, as well, they find that she cannot become pregnant (meanwhile, Leah has no trouble producing children). Rachel then gives her handmaid, Bilhah, to Jacob, so that Rachel can have children “through” her. Bilhah’s voice is never heard in the bible.

In another instance in the Old Testament, Hagar, a slave purchased in Egypt, is given by her ‘master,’ Sarah, to Abraham, to conceive an heir (read more about this story and its interpretations here). Finally, in the New Testament, Mary declares herself “the handmaid of the lord” while accepting the immaculate conception of Christ.

The Handmaid’s Tale is often classified as dystopian, futuristic fiction. But learning more about myths from the past that inspired the story makes me realize that past, present, and future are not as separate as we might think.

All myths are stories, but not all stories are myths: among stories, myths hold a special place. —Margaret Atwood, In Other Worlds: SF and the Human Imagination

More on Margaret Atwood and Retellings

- is on Substack. Her writing is, as one would expect, excellent.

How Margaret Atwood Redefined Mythology Through Her Feminist Retellings in The Curious Reader, a literary magazine

A perfect storm: Margaret Atwood on rewriting Shakespeare’s Tempest from The Guardian

The essential Margaret Atwood reading list from Penguin UK

— Shruti

Next Up

Next on the podcast, we’ll be reading and discussing American Gods by Neil Gaiman. The episode will come out on March 20.