Theater & the Novel, Part I: 19th Century Drama, Key Elements of the Novel, and Books Inspired by Plays

How theatrical traditions influenced the development of the novel

Last week on the podcast, we discussed Home Fire by Kamila Shamsie. Though I didn’t love it on first finishing it, the longer I let it sit, the more I appreciated what Shamsie was trying to do and the more I understood how well it works as a retelling of Antigone.

In our episode, Neha talked about how the book is structured around the idea of fives, or a pentad: there are five main characters, each of whom is given a section of the novel, mimicking the traditional five-act structure of classical drama.

It got me thinking about the links between the novel and theater, and how the two forms have evolved in parallel over millennia, each borrowing from, and influencing the other in countless ways.

Theater & The Novel: Before the Forms Diverged

The form of the novel began to rise in popularity in the 18th century in the Western English-speaking world, in tandem with increasing literacy and the spread of the printing press (though, of course, the novel has been around for centuries in other parts of the world).

At the time, theater was still a popular form of entertainment and instruction; and as the use of print media increased, it started to pervade the theater. Books of the play were published with prologues and epilogues, ‘dramatic intelligence’ about plays and actors appeared in newspapers and journals, and theater pamphlets themselves were distributed to theater-goers.

Plays and novels often coexisted in public spaces: circulating libraries stocked dramas and novels side by side on their shelves.

And as the written word spread, ‘closet’ dramas developed — plays designed for private reading rather than performance. And conversely, novel-reading was not yet the solitary activity we imagine it to be today. Many gentry families would read novels aloud to groups, creating an intimate theater of performance.

Slowly, over time, the novel began to emerge as an independent form; one with distinct advantages over the theater, which not only had to appeal to a vast and diverse audience, but had rigid rules regarding length (performance time) and, often, subject matter.

But the influence of the theater remained.

Aristotle’s Poetics: Key Elements of the Novel

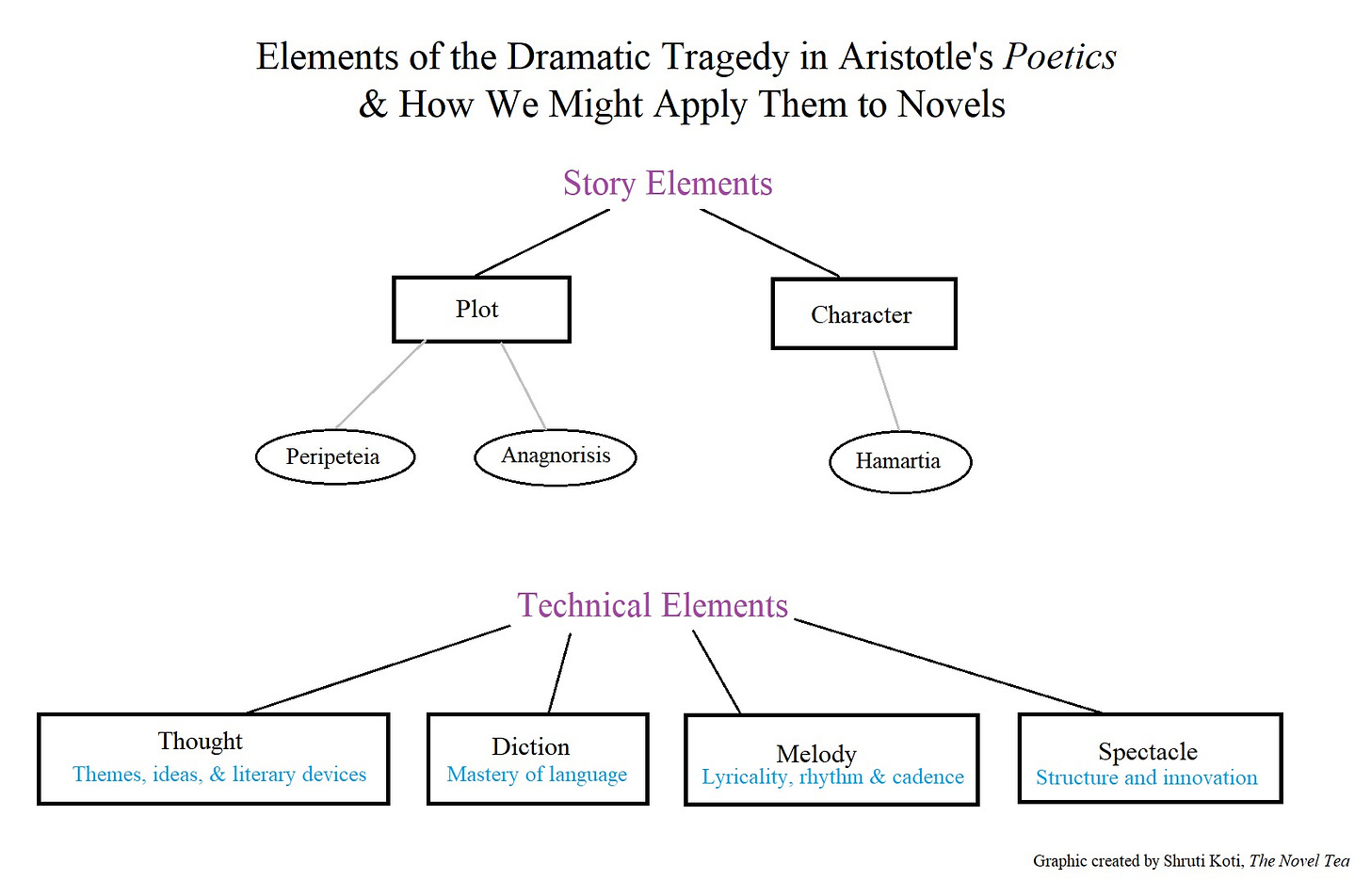

The way we conceive of novels today has a lot to do with what Aristotle believed a good tragic drama should achieve. Written around 355 BCE, Poetics differentiates between tragedy and comedy in its exploration of drama — though Aristotle believes tragedy to be the superior form.

The elements he then explains form the basis of our understanding of the novel today (and therefore, as Matthew Salesses argues in Craft in the Real World, we should question these assumptions, and ask what tradition they are sustaining).

Plot and character are familiar to us — plot as an arrangement of incidents and actions in a narrative work (and which Aristotle says should have a clear beginning, middle, and end), and character as the moral qualities and traits of people within a dramatic work.

But within these two components, there is more:

Hamartia: a tragic flaw or error in judgment that leads to the downfall of the tragic hero (fans of The Secret History will recognize this element)

Peripeteia: a sudden reversal of fortune or circumstances, usually from good to bad, in a tragic hero’s journey

Anagnorisis: the moment of recognition or discovery, often when the tragic hero realizes their own error or true identity

Aristotle believes that peripeteia and anagnorisis are essential components of complex plots.

But there is more to story than just plot and character. There’s also:

Thought: ideas, themes, and arguments expressed in a dramatic work

Diction: the choice and arrangement of words in a dramatic work

Melody: musical elements such as chorus and songs in a tragedy

Spectacle: the visual and physical elements of a work, such as costumes, sets, and special effects

Of course we should question these elements, and recognize that they are operating within a very specific, Western tradition (of tragic drama, not novels!) — and yet. I couldn’t resist making a graphic. Because I think these elements can be translated into the way we, in the modern Western world, understand novels.

(As an aside, I think we as readers ascribe different levels of importance to these six elements — and based on the elements we care most about, our tastes trend in different directions.)

Despite Aristotle being long dead, the legacy of theater influencing the novel hasn’t gone away.

Theater Retellings & Books Inspired by Plays

What is it that novels do that theater cannot? In our upcoming episode about adaptations, we talk all about adaptation theory and the strengths of different forms (that episode will be out June 25th).

The most obvious answer is interiority — we can get into the thoughts and emotions of a character in a way that we cannot on the stage or on the screen. But there are other advantages, too. A novelist can stretch time, manipulate it, reverse it, and jumble it up. A novel can be verbose or spare. A novel can spark and engage the reader’s imagination in an individualized way.

Here are some books inspired by the theater that, as we talked about in our introduction episode to our adaptations season, adds to or enhances the original story in some way:

Home Fire by Kamila Shamsie

Our most recent podcast selection, Home Fire, is a retelling of Antigone set in modern day England, Syria, and Pakistan Those familiar with the family dynamics and political backdrop of Antigone will appreciate the choices Shamsie made to recontextualize the story — the three siblings, Anika (Antigone), Isma (Ismene), and Parvaiz (Polyneikes) are the children of a man who was an enemy of the state. Karamat (Creon) is the UK Home Secretary, and when Parvaiz abruptly leaves the country to join an extremist organization, the story’s characters are thrown into chaos.

In our podcast discussion, we explore the ways in which this adaptation stays true to the original story, while shifting its focus and highlighting different themes. Shamsie pays homage to theatrical traditions by mimicking a play’s five-act structure, and focusing on a small, intimately connected cast of characters.

A Thousand Acres by Jane Smiley

A retelling of King Lear, this Pulitzer winner follows the story of Larry Cook, a farmer in Iowa who divides his farm between his three daughters, until the youngest, Caroline, objects and removes herself from the agreement. Dark truths come to light as the family cope with reality of life in the midwest.

While I personally found this book a bit boring and tedious (it didn’t seem to be asking any new questions when compared to King Lear, nor was it treating the questions raised by the original play in a different way), obviously Smiley, as a winner of the Pulitzer, does not need my endorsement.

The Penelopiad by Margaret Atwood

Alright, fine, The Odyssey is an epic and not a novel — but Greek epic has influenced the modern novel in many ways. The Penelopiad is a retelling of The Odyssey from Penelope’s perspective, and from the perspective of the twelve hanged maids.

While nowadays there is a plethora of myth retellings, The Penelopiad was probably one of the first to really center women in a retelling of Greek myth. We talked all about it on Season 3 of our podcast, Other Worlds.

House of Names by Colm Tóibín

A retelling of Aeschylus’ Oresteian Trilogy, House of Names follows Agamemnon as he sacrifices his daughter on the way to battle — when he returns three years later, he returns to find how his murderous action has impacted his entire family. His remaining children, Electra and Orestes, must find a way to right the wrongs of the past.

I haven’t read this one yet, but it sounds fascinating — I read Iphigenia in Aulis in college and loved it, and I haven’t yet reached my limit with myth retellings.

Even more lists and recommendations:

The Best of the Bard: Nine Literary Works That Radically Reimagine Shakespeare [Lithub]

10 Shakespeare Retellings Adapted for the Modern Era [Electric Lit]

Let us know what you think: what are your favorite novels inspired by plays?

Next week: even more about theater & novels! In part 2, I’ll talk about when theater and plays feature heavily within a novel, with, of course, lots of book reflections and recommendations.

— Shruti

References:

Russell, Gillian. “Chapter 28: The Novel and the Stage.” The Oxford History of the Novel in English, vol. 2, Oxford University Press, 2015, pp. 513–531.

“Aristotle’s Poetics.” Literary Latitude, 2 Feb. 2025, literarylatitude.com/2025/02/02/aristotles-poetics/.

Links We Love

- - a great exploration of allusions in Piranesi, and the ways in which the book is in conversation with C.S. Lewis’ novels and philosophy

Invisible Man, Fashion, and the Met Gala by

- an essay looking at Ralph Ellison’s novel and the 2025 Met Gala with its theme of Black Dandyism- - a fascinating deep dive into the experience of reading Wuthering Heights, including the ways it is in conversation with Shakespeare, its philosophy, and its Gothic motifs.

Latest on The Novel Tea:

Next week we’re discussing All’s Well by Mona Awad — which is both a retelling of Shakespeare plays, and contains a play within a novel. Reading this book was a wild read, and you won’t want to miss hearing all of our insights and reactions! Tune in on June 11 wherever you get your podcasts.

And if you missed our recent newsletters, we talked all about color theory in films, how the novel of manners is a descendant of theatrical comedy, and three very different novels of confinement:

Thanks for the shoutout! Loved this article--adaptations and genre are so fun.