Shapeshifting Spirits: the Evolution of Ghosts in Literature

Who are they, and what do they represent?

Last week on the podcast, we talked about The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen. At different points in the narrator’s journey (often when he least suspects it), he is visited by ghosts. At some times, they seem like apparitions — at others, like memories.

But unlike many other stories that feature ghosts, The Sympathizer is decidedly not horror. Nor is it a ‘scary story’ (in the traditional sense, anyways). I wouldn’t even call it magical realism. It got me to thinking —

What do ghosts do in novels? Who are they, and what do they represent?

Note: if you are reading this in your email inbox, it might get cut off at the bottom — just click ‘continue reading in browser’ or ‘view entire message’

An Ancient Warning

In 2021, an ancient Babylonian stone tablet from 1,500 BC was discovered in the vault of the British Museum, becoming the oldest known depiction of a ghost. On its surface, a lone bearded spirit is led forward into the afterlife by his lover.

The tablet directs the reader to create figurines of a man and woman. The man should be dressed in regular clothing, and carry travel necessities. The woman should wear four red garments and be draped in a purple cloth. Give her a golden brooch. Provide her with a bed, chair, mat, and towel. Give her a comb, and a flask.

At sunrise, set up two vessels of beer. Place the figurines along with their accoutrements in a precise position. Finally, call to the Mesopotamian god Shamash, responsible for bringing the ghosts to the underworld. By following these instructions, one can get rid of a ghost that “seizes hold of a person and pursues him and cannot be loosed.”

But in the final line of the tablet, a warning is inscribed:

“Do not look behind you!”

The First American Ghost Story

Around the world, across cultures, ghosts have appeared throughout history. In ancient times, they often appeared when a person was not properly buried; the apparitions were a reminder and a threat to respect the dead.

Today, despite all our advances in science and technology, despite the Age of Enlightenment, ghosts persist in legends, mythology, pop culture, and literature.

The first recorded haunting in the United States took place in the winter of 1799, when one Captain Abner Blaisdell started hearing strange noises in the cellar. A few weeks later, a voice started talking directly to the inhabitants of the house. One day, finally brave enough to talk back to the voice, Captain Abner asked who she was, only to hear, “I am the dead wife of Captain George Butler, born Nelly Hooper.”

Nelly Butler was a woman from a nearby house who had passed away three years earlier during childbirth. As time went on, dozens of others in the county came forward as witnesses to the voice, until townspeople were convinced that the spectral voice was some kind of demon.

As the story goes, Nelly Butler wanted to speak with her former husband to help him remarry — but once she finally did, she put forth a warning: “Be kind to your wife: for she will not be with you long. She will have but one child and then die.”

The Novel Tea Newsletter is a companion to The Novel Tea podcast, where we aim to discover and discuss diverse books to create our own canon of classics. Listen to the podcast here.

To get essays like this, literary analysis, book recommendations, and cultural commentary, subscribe for free:

Ghosts as Fear of the Past

For years, the appearance of ghosts in literature has implied a haunting; a representation of a disturbing past that must be vanquished. We see this in Hamlet, as the dead king appears to bring Hamlet to action and avenge his death. Or in Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White, when a mysterious woman, wearing all white, is seen in rural areas and assumed to be a harbinger of tragedy.

Ghost stories exploded out of the Victorian age, published as sensational fiction that was meant to scare, entertain, or moralize. They are everywhere in Gothic fiction, both traditional and modern; even when they don’t appear as translucent embodied figures, their presence can be overpowering (think Rebecca — if a ghost isn’t another physical being that can be seen and touched, is it really an external presence, or is it just a creation of your own mind?)

Ghosts are necessarily tied to death, and our understanding of it. In George Saunders’ Lincoln in the Bardo (the term ‘bardo’ comes from a concept in Tibetan Buddhism), 166 ghosts exist in the space between life and death. Importantly, very few of the ghosts will admit (even to themselves) that they are no longer alive. They are all tied to this world, unable to move on — to such a degree that their physical appearances are shaped by their regrets and misdeeds.

“Trap. Horrible trap. At one’s birth it is sprung. Some last day must arrive. When you will need to get out of this body.”

The ghosts are direct representations of the people that they once were — and so they are preoccupied with their own individual motivations and desires, tethered by grief and regret.

But sometimes, the past itself can be a powerful character.

In a New York Times essay about ghost stories, critic Parul Sehgal1 writes: “…ghost stories are never just reflections. They are social critiques camouflaged with cobwebs; the past clamoring for redress.”

And as time has gone on, the way ghosts have appeared in literature — and the way we’ve interpreted them — has expanded. They don’t always represent an individual person who has died; rather, they can symbolize memory and the past on a larger scale.

In The God of Small Things, a postcolonial novel set in Kerala, India, Arundhati Roy uses Gothic conventions to create a dark atmosphere and represent the broader horrors experienced by a whole country as a result of imperialism and political violence. The ghost of a moth haunts one of the children, carrying the guilt and trauma of his ancestors onwards to younger generations.

Here, I wish I could reference Beloved, and talk about how the ghost in that story is both the form of a loved one and a representation of the traumatic legacy of a nation, but sadly I haven’t read it yet (though it is high up on my TBR).

Ghosts as Memory and Comfort

As we have moved into a modern era (and broadened our reading beyond the Eurocentric canon) the representations of ghosts have shifted, too.

While earlier European novels used Gothic conventions to inspire fear, desire, and enact revenge, many newer novels using ghosts might fall more into the realm of magical realism (which is a genre label that I have mixed feelings about). Spirits abound, but they don’t exist in order to scare characters into behaving better.

The narrator of The Sympathizer is visited by three ghosts over the course of his story — these three ghosts do represent real people that he knew, but their presence in his life is not negative, nor is it spooky. In fact, the ghosts seem to be one of the only things that have any emotional resonance with the author, reminding him, often at the worst times, of who he truly is.

A similar phenomenon occurs in The Night Watchman by Louise Erdrich. In the sections about Thomas, the night watchman, we get interludes about Roderick, a former classmate who now appears from time to time as a ghost. Thomas initially thinks that Roderick’s appearances have to do with his own role in Roderick’s death — but definitive answers are never provided.

Instead, we see, in several ways, how the characters’ lives are peppered with other worldly phenomena. The ghosts in this story remind us of a troubled past, but they also exist as guideposts for the living, and, in a way, represent memory itself.

Earlier this year, I read Let Us Descend by Jesmyn Ward. The book follows Annis, a young enslaved woman who is the daughter of a Black woman and her white enslaver. Every month, Annis and her mother practice spear fighting in the shade of the forest. Her mother tells her stories of her grandmother, Mama Aza, an African warrior, recalling her ancestors’ ways of living.

As Annis travels across counties, sold to one slave owner after another, experiencing horror after horror, spirits start to appear to her. These spirits give her strength, and help her to make sense of her world.

One, whom she calls Mama Aza, takes the form of the natural world around her:

“Her skirts are not silk, not cotton spun fine, but are obscure and full as high summer clouds, towering in the sky, boiling toward breaking. What I thought was a cape is tendrils of fog draped over her shoulders, yielding curtains of rain down her arms.”

The ghosts in Let Us Descend are different from what we might be used to. In the European Christian tradition, ghosts and spirits are often representative of a particular religious ideology. But here, they are Annis’ own people, her own memories and generational legacy.

It seems that as we expand our canon of literature to authors from a variety of countries, cultures, and traditions, the way we understand literary ghosts starts to grow. Their symbolic meaning is no longer limited to one form or genre.

In the aforementioned New York Times essay, Sehgal writes: “The ghost story shape-shifts because ghosts themselves are so protean — they emanate from specific cultural fears and fantasies.”

And so the way we represent and understand ghosts will continue to change — reflecting our ideas and priorities as a culture, morphing over time, always fluid.

Which literary ghosts stand out to you, and what do they mean?

— Shruti

Further Reading:

How Literary Ghosts Can Help Us All Be a Little More Human [Lithub]

The Ghost Story Persists in American Literature. Why? [NYT]

Related Posts

If you loved this comparative discussion tracking a symbol across multiple books, check out these other essays we’ve written on liminal spaces in literature, and the symbolism of birds in books:

Up Next

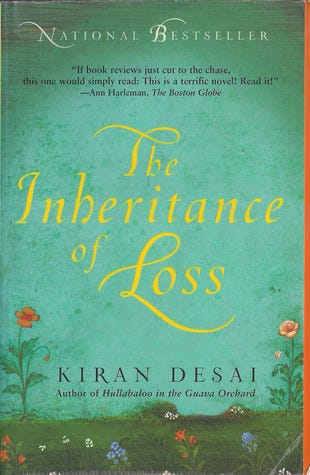

Next on the podcast we’ll be discussing The Inheritance of Loss by Kiran Desai. This book, set in a small town at the foot of the Himalayas, won the Booker prize in 2006. We follow four characters in India and abroad in the 1970s, watching their worlds collide as the consequences of colonialism loom large in their lives.

The episode will be out next week, on September 18th.

Parul Sehgal also wrote an excellent essay titled “The Case Against the Trauma Plot” which we talk about more extensively in our episode on global literature and trauma narratives.

Loved this essay! And you absolutely have to read Beloved, I think you'll really enjoy it

I loved seeing the still from Rebecca in this post ... the novel by Daphne Du Maurier is one of my favorite books ever, and the 1940 film is a great interpretation, though because of the Hayes code they had to change one pretty important plot point.