“Last night I dreamt I went to Manderley again.”

What a line!

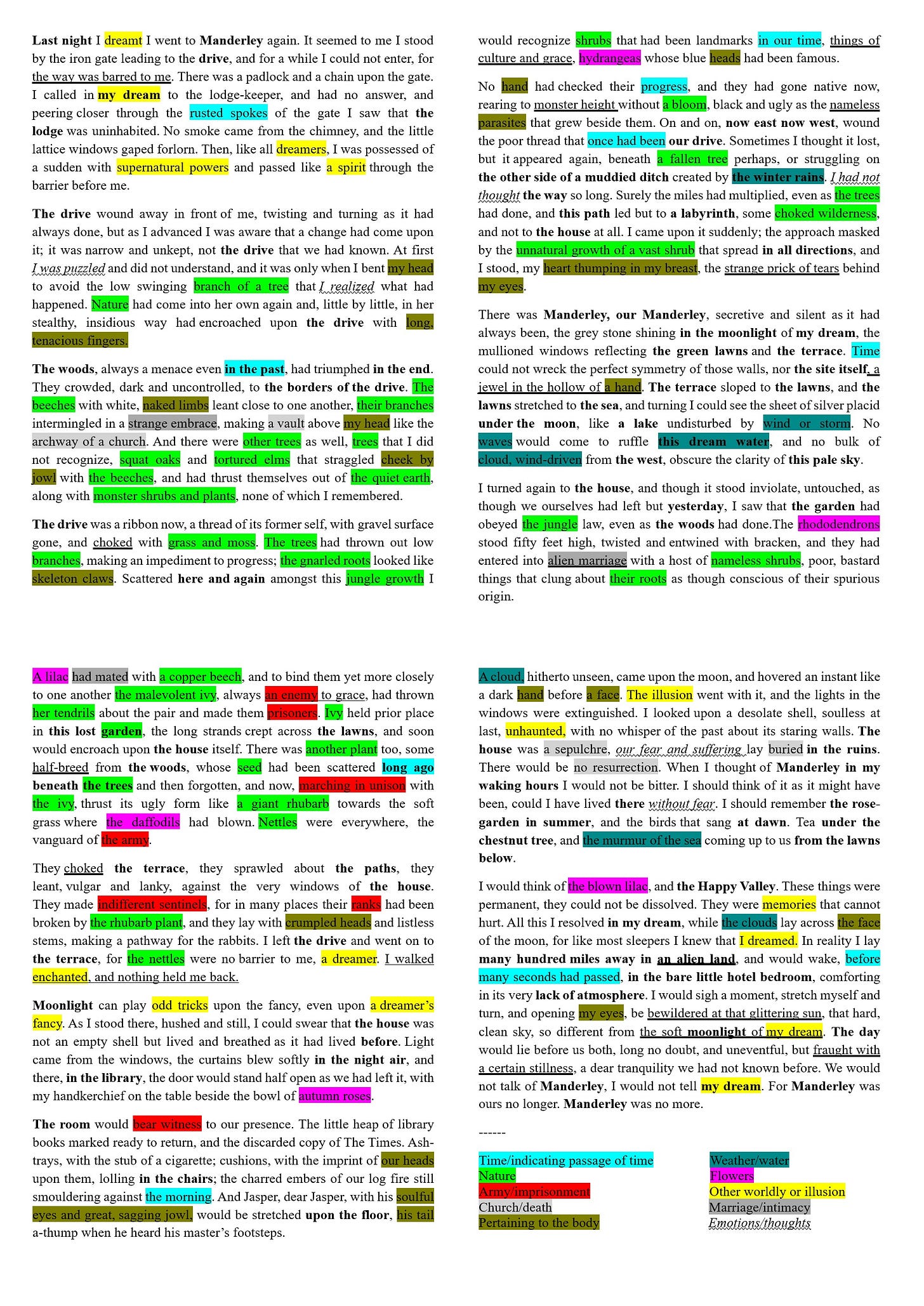

Lately on The Novel Tea podcast, we’ve been discussing Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier. In our book discussion, I said that if anyone ever wanted to learn how to write a perfect first chapter, they need only read the beginning of Rebecca (you can hear the full podcast episode here). And in today’s newsletter I’d like to put my money where my mouth is — by showing you how brilliant du Maurier’s writing is. (This essay is spoiler-free so read on without fear!)

If you read last week’s newsletter, you know that we are restructuring The Novel Tea Newsletter (which is why you’re getting this post on a Wednesday), and offering an exciting new series for paid subscribers: Spill the Novel Tea. In these installments, you’ll hear all about the books Neha and I are reading, our reflections, and how they might be in conversation with one another.

For a limited time we are offering a discount on paid subscriptions. Upgrade now for 20% off the entire year, and to get our first installment of Spill the Novel Tea!

First, a bit about the way I read: I don’t have any particular method for annotating — sometimes I get very intense, developing multiple symbols to put in the margins, and having up to twelve colored tabs representing various themes and motifs. Other times, all I have is a pencil, and I just underline sentences that sparkle up at me. Often, I don’t annotate at all.

But a book like Rebecca deserves some close attention.

You can read a clean version of the first chapter here, or through Goodreads or Google Books previews.

The first thing that stands out to me is how little we get of the narrator’s emotions — despite this book being told in the first person, the only named emotions come towards the end: “our fear and suffering” and “without fear.” This is important: even though the narrators seems to describe her love for Manderley, we are never given any positive emotions in the description.

The next thing I notice, as I look at the distribution of the various colors from afar, is that there are no references to nature or wilderness in the first and last paragraphs. These are also the only two paragraphs in which Manderley is named. And each time she mentions ‘Manderley,’ it is accompanied by mention of a dream.

“We would not talk of Manderley, I would not tell my dream.”

It’s almost as if ‘Manderley’ is a separate place, time, or realm, than the house, or its terrace, and its lawns (which she does refer to frequently when describing the estate’s natural elements). From the very first page, du Maurier is setting us up to question the narrator’s presence at Manderley, whether the place is real, and whether her experience there was real.

Another hint that perhaps everything we are about to read is an illusion (or, at the very least, should be questioned):

“A cloud, hitherto unseen, came upon the moon, and hovered an instant like a dark hand before a face. The illusion went with it, and the lights in the windows were extinguished.”

(And while we’re thinking about clouds and moons, consider the “bewildered at that glittering sun” with “the soft moonlight of my dream” in the last paragraph — this is the only mention of sun in a chapter otherwise filled with imagery of clouds and the moon. It is tempting to think that the “glittering sun” is a sign of a bright future, but… in this paragraph she also says that her new home is “comforting in its very lack of atmosphere.” I don’t know about you, but that sounds rather bleak to me.)

One thing that strikes me about dreams in this chapter is that they are both setting and phenomena; ie, a dream is the place in which the story unfolds, but it is also a thing happening to the narrator, something she cannot explain.

This first chapter is packed with descriptions of nature and wilderness — and notice how nature is personified:

“Nature had come into her own again and little by little, in her stealthy, insidious way had encroached upon the drive with long, tenacious fingers.”

This is the first, but definitely not the last, mention of body parts. The references to body parts are carefully placed: the body parts mentioned in reference to the narrator are vital organs, or sense organs: “heart thumping in my breast”; “my eyes”; and “a face.” But the body parts mentioned in reference to the forest (and, one can extrapolate, Rebecca)1 all relate to limbs and bones: “tenacious fingers”; “naked limbs”; and “skeleton claws.” This contrast shows how the narrator can only react to things, while all the action is happening through the forces of Manderley (or Rebecca).

The mention of bones and limbs also conjures up the image of a skeleton. There are other motifs that reinforce this idea: I found many so references to churches and graveyards, as well as words pertaining to the army and imprisonment.

My favorite motif in any book has to be flowers — and in this book, especially, they are so important!

“The rhododendrons stood fifty feet high, twisted and entwined with bracken, and they had entered into alien marriage with a host of nameless shrubs, poor, bastard things that clung about their roots as though conscious of their spurious origin.”

Okay, there is so much going on in this line (check out my annotations above for more detail).

First of all, we learn later in the novel that rhododendrons are meant to remind us of Rebecca (in our podcast episode we get deeper into this symbol and the meaning behind rhododendrons). And “nameless shrubs, poor, bastard things,” of course, reminds us of the narrator! She is nameless, poor, and for all intents and purposes, a bastard — she doesn’t know her parentage.

So while at first glance one might imagine that the “alien marriage” is between Max and the narrator, or between Max and Rebecca, we can see now that the alien marriage is in fact between the narrator and Rebecca. This is fascinating — because what would such a marriage mean?

And for that matter, when du Maurier writes “nameless parasites” are we meant to understand that the narrator herself is something of a parasite? For this is indeed not far from how she sees herself when she first arrives at Manderley.

As mentioned before, the penultimate paragraph is the only one in which any emotions are named (“our fear and suffering” and “without fear”) — but still, we don’t get the narrator’s actual thoughts emotions as they are happening, but rather, what might be: “I would not be” and “could I have lived there without fear” and “I should remember.”

What are we to make of this richness of description so devoid of emotion?

I have explored just a few interpretations above, but there are so many other things that you can pick up on in this incredible first chapter — and probably an infinite amount in the whole book!

What is your favorite detail in Rebecca?

— Shruti

P.S. Thank you to

for sharing her method for annotating on a computer! I typically only do it with a pencil on physical books, but Haley’s tips helped me create a method to annotate on a Word document, so that I could share my close reading with you all today.More on Rebecca

Beautiful in its contradictions: on reading Rebecca by Daphne Du Maurier -

writes about the many contradictions and opposing ideas in the novel.Thoughts on Rebecca by Daphne du Maurier -

compares some of the themes in Rebecca to those in the classic film GaslightThrough the Writer's Lens: Rebecca -

breaks down du Maurier’s techniques, exploring how she creates tension and atmosphere, and offering exercises for those hoping to improve their craftHow to Read a Fire: On Hitchcock’s Rebecca - an analysis of the visual elements of the 1940 movie, including the three approaches to Manderley, and the closing scene

Rebecca: Movie Adaptations - our latest podcast episode, in which we talk all about the 2020 movie (directed by Ben Wheatley) and the 1940 Hitchcock film.

So You Want to Start Close Reading:

Confession: I learned basically nothing about close reading and literary analysis from my college lit classes — most of what I’ve learned has come in the years since, from diligent reading and re-reading, being ceaselessly inquisitive and, more recently, perusing some excellent online sources. Here are some that have helped me become a better close reader:

- breaks down how to close read and annotate at the sentence level

defining your annotation style:

at it again with more excellent tips!Issue 80: The no-bullshit guide to annotating your books:

shares some very simple, approachable ways to engage with your booksReading in Public No. 64: Low effort, high reward strategies for better annotations:

lists three no-stress tips for better annotations

One of the themes we paid attention to in our reading of Rebecca was wildness. In our discussion, we talked about how Rebecca is represented by the untamed vegetation and natural features of Manderley.

i love this, thanks for your work here!

i read rebecca for the first time last year (to prep for my own rebecca post: https://therollingladder.substack.com/p/rebecca) and enjoyed comparing/contrasting the book to jane eyre: the narrators, max vs rochester, the ghost vs the madwoman, manderley vs thornfield, grace poole vs mrs danvers etc. its so rich and damn i love a gothic!

Perfect analysis and gorgeous post as usual 😎 It makes me want to re-read Rebecca asap!