Bear With Me

Where we discover bear mythology across the world

Last episode on The Novel Tea podcast, we discussed Daughters of the Deer by Danielle Daniel. In this episode, I talked about how the re-occurrence of a bear throughout the story shows us the difference in characters personalities, thoughts, and beliefs. The bear symbolizes many things in Native American culture, but we specifically touched on its metaphor for protection, healing and strength. When talking about this, I remembered the symbolism of the bear in The Night Watchman by Louise Erdrich that we discussed in season one of The Novel Tea podcast as well.

Bears are animals that come up pretty frequently in mythology and folklore, not only in indigenous stories. Connecting the similarities of what bears mean in these stories led me down a bear-shaped rabbit hole of what they may symbolize in other cultures.

You are reading The Novel Tea Newsletter, companion to The Novel Tea Podcast, where you’ll find book reviews, thematic literary analysis, and cultural commentary to help you thoughtfully engage with the world.

New posts come out every Tuesday. If you enjoy reading our work, please consider subscribing and sharing the newsletter with others.

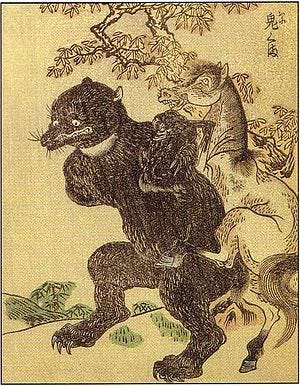

Okinuma

Okinuma is a bear type spirit found in Japanese folklore. It was first seen in a book called Ehon Hyaku Monogatari (Picture Book of a Hundred Stories) written in 1841 by multiple Japanese authors with wood block pictures.

Okinuma (directly translates to “demon bear”) are bears that have transformed into yokai (or supernatural entities) because of their old age. They are massive bears with inhuman strength that walk upright and sneak into villages at night to steal food and livestock. Large stones in the Kiso Valley are called Okinuma stones because of their size and placement, local tradition has said that these bear monsters would throw these stones at humans from the mountains above.

“A legend says that a group of villagers once hunted and killed an onikuma. They were sick of their horses being carried off, and tracked the onikuma back to its cave lair. In preparation, they carved long spears from massive trees, and placed fresh meat as bait in front of the onikuma’s cave. When it came out for its supper, the villagers attacked with their long spears, killing it. They took the carcass back to their village where they stretched and tanned the hide. It was said to be big enough to cover the floor of an entire large room.”

— by Zack Davisson in From Mizuki Shigeru, Magical Animal Stories, Yōkai Stories1

Artio

Artio is a prominent figure in Celtic mythology and is commonly depicted as a bear which symbolizes her connection to wilderness and transformation. Her presence goes all the way back to 450 B.C. to a Celtic tribe in Switzerland. It is believed that Artio accompanied members of this tribe on their journey to Western Europe.

Her origins could be even older than that. Some feel that the bear is the oldest European deity as bones and skulls of bears have been found lovingly arranged on niches found in caves across Europe. In 1840 in Ireland, during the restoration of Armagh Cathedral, ancient, small stone carvings of bears were found.

Further evidence of Artio’s ancient origins is found in the first written sentence from the “Old Europe Script”, invented around 6,000 years ago, long before the Celts arrived. It reads ‘The Bear Goddess and the Bird Goddess are the Bear Goddess indeed.’2

In further studies of Artio, Joseph Cambell found significant connections to Artio and Artemis (Greek goddess of hunting and nature). On The Novel Tea podcast a few months ago, we did a deep dive of mythology and talked a lot of Joseph Cambell and his works (listen to the episode here).

Joseph Campbell, in his Historical Atlas of World Mythology, concludes that Artio is the Celtic sister of the Greek Goddess Artemis, who is also associated with bears.

Campbell also explores Artio’s connection to the heavens by connecting Her and the long line of bear cults to the constellations of Ursa Major and Ursa Minor, the Great Bear and the Little Bear (which contain the Big Dipper and the Little Dipper). The brightest star in Ursa Major is Arcturus which is Greek for “bear watcher” or “guardian of the bears.”

Campbell writes of these constellations – they are “revolving forever as constellations around the Pole Star, axis mundi of the heavenly vault”. In the same way Artio was perhaps seen as strong and enduring – as the center and the connection between Heaven and Earth.3

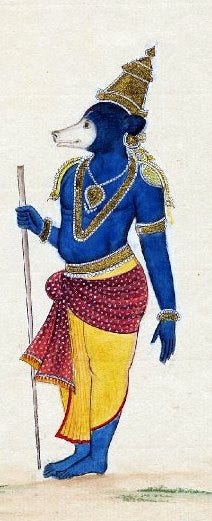

Jambavan

Jambavan is a king of bears that is seen in Hindu texts as a part of The Mahabharata and Ramayana. Shruti and I had many discussions about The Mahabharata while reading The Great Indian Novel by Shashi Tharoor (episode here), The Palace of Illusions by Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni (episode here), and even did our own deep dive of the Mahabharata in its own episode.

Jambavan is said to be birthed by Lord Bhrahma himself, to aid Lord Rama against the demon king Ravana. Jambavan plays multiple roles in the overarching story of The Mahabharata and Ramayan.

One of these stories says:

According to Kamba Ramayaṇa, at the time of the incarnation of Vamana, Jambavan was very strong and valiant. When Vamana brought under control the three worlds by measuring three steps Jambavantha traveled throughout the three worlds carrying the news everywhere. Within three moments, Jambavan traveled 18 times through the three worlds. In this travel of lightning-speed, the end of the nail of his toe touched the highest peak of Mahameru, who considered it an insult and said, “You are arrogant of your speed and youth. Hereafter your body will not reach where your mind reaches, and you shall be ever old.” Because of this curse, Jambavan became old and unable to carry out what he wished.4

These are very few examples of cultural depictions of bears. For further reading, you can check out the links below!

—Neha

Indigenous Historical Fiction

Exploring older time periods: pre-Columbus, Native-settler relations, and Civil War time

The Birds and the Books

Tracking symbolism through Jane Eyre, The Illness Lesson, Taylor Swift, and more