It was in a conversation with Neha during one of our recording sessions that I suddenly realized: aliens coming to Earth to destroy humanity felt a lot like colonial settlers coming to a ‘new land’ and destroying the native population.

We talked a bit about this concept on our recent episode on The Left Hand of Darkness, which you can listen on your podcast platform of choice — and while you’re listening, please consider leaving us a rating (takes 2 seconds) or a review (5-120 seconds depending on how verbose you are). Currently, our reviews represent a teeny tiny fraction of our listeners (<5%!), and we know there are more of you out there. Ratings and reviews help SO MUCH by increasing visibility and allowing others discover the podcast. We are a small independent podcast and we need your support to grow — thank you!

Alright, back to colonialism — as we talked about our two science fiction picks for the season (The Humans and The Left Hand of Darkness), I grew more curious, so I decided to do some research.

As I suspected, I am not the only person to have drawn a connection between science fiction and colonialism.

In the book Colonialism and The Emergence of Science Fiction, John Rieder describes how when the Copernican shift occurred, going from a geocentric idea of the universe to a heliocentric solar system, our conception of other potential worlds started to grow. As new areas of knowledge started to grow, fields such as evolutionary science and anthropology often found their way into novels and artistic representations of the world.

Science fiction, at least in the Western world, first appeared in countries that were significantly involved in imperialism: France and England. It grew as a genre in tandem with colonial expansion, and in the 20th century, spread to the US, Germany, and Russia, as these countries became more politically involved with one another.

…we must remember what ruthless and utter destruction our own species has wrought, not only upon animals, such as the vanished bison and the dodo, but upon its own inferior races. The Tasmanians, in spite of their human likeness, were entirely swept out of existence in a war of extermination waged by European immigrants, in the space of fifty years. Are we such apostles of mercy as to complain if the Martians warred in the same spirit?

This passage appears in the first chapter of The War of the Worlds, by HG Wells, and in these lines he references not only racism and colonialism, but also eugenics. He then draws a direct comparison between the mass genocide of humans by other humans, and an alien invasion.

And even though he somewhat inverts it, turning the threat back onto Europe, doesn’t that represent a deep-set anxiety that someone will do to white people what they did to others?

This idea of the “other” crops up across genres and media, and is certainly not new. We can go even further back to texts like Gulliver’s Travels to find descriptions of encounters with foreign nations and alien peoples.

You can read more about Rieder’s ideas in this interview.

What’s Up with the Names in Science Fiction & Fantasy?

I know I’m not the only one to find names in sci-fi, dystopian, and fantasy novels unique and interesting. Last week, Neha explored some of Ursula K. Le Guin’s methods for creating place and concept names in The Left Hand of Darkness:

Going beyond this book into the realms of fantasy and science fiction, I was excited to learn more about naming conventions. Many of the names we encounter seem to spring from Eastern languages and word roots — the whole thing reeks of orientalism — and I was sure there would be an abundance of scholarship looking into how these names, taken from ‘Oriental’ cultures, served to create a kind of “other.”

And yet, to my surprise, I just hit dead end after dead end. I spent hours upon hours searching on Google, looking on Jstor, and combing through academic publications to no avail (why is this? If anyone knows where to find scholarship on this topic, please share!)

Instead, I encountered a LOT of discourse about Dune (books and movies), Islamophobia, and language. I haven’t read the books (nor have I seen the movies yet) but I still found these articles fascinating, and I hope you do too:

Epic World-Building: Names and Cultures in Dune - Kara Kennedy describes how inspiration from Middle Eastern cultures plays a crucial role in the worldbuilding and relational dynamics in Dune.

“Dune” and the Delicate Art of Making Fictional Languages - article in the New Yorker about the role language plays in the world of Dune, and how Herbert Frank pieced together the words he used.

Erasing Arabs from “Dune”: when is a gift not a gift? - in this essay, a scholar at the Middle East Institute chronicles the erasure of Arab elements from the new movie with reference to the 1984 movie.

The Failed Worldbuilding of Villeneuve’s Dune - more detailed thoughts on how the worldbuilding in the new Dune movies fails in comparison to the book by

on Substack.The novel ‘Dune’ had deep Islamic influences. The movie erases them. - in this article from the Washington Post, the role of language and cultural terms is explored.

Just call it Jihad - written by Substacker

about how the Hollywood-ization of Dune and 3 Body Problem has revealed persistent, infuriating racist tropes that are still alive and well in the industry.

— Shruti

Up Next

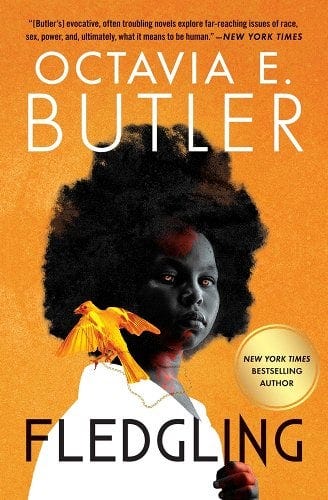

Tomorrow on The Novel Tea Podcast, we will be discussing Fledgling by Octavia E. Butler, a book about a 53 year old Black vampire who is on a journey to find out the truth of who she is.

This book was not at all what we expected, and we had a tough time with parts of it; but by working through our thoughts, we broke through to some incredible revelations, and we can’t wait to share them with you.

Tune into the conversation tomorrow, May 7th!