Books from Around the World, Disability, and Trauma Narratives

S2E14 | Global Reads: Wrapping up Season 2

We are already wrapping up Season 2 of our podcast - and what a season it was! We had so many thoughts on representation, post-colonial writing, and the kinds of stories POC authors get to tell. In this newsletter we expand on these topics, and share some unique book recommendations you may not have heard of before!

In our Season 2 Wrap-Up episode, we talked about the books we’ve read over the past few months, considering the voice of children, heroes and villains, how disability is portrayed in literature, and colonial and post-colonial writing. We also did a deep dive into trauma narratives - why are they so popular nowadays? What stories are being promoted, and how does this limit the perspectives of authors of color?

Below we’ve included extra content that we just didn’t have time to get to on the podcast episode, including: perspectives on trauma writing, disability representation in popular culture and writing, and books from other countries that aren’t just about trauma.

Perspectives on Trauma

As we wrapped up Season 2, we reflected on how frequently themes of trauma and violence came up in books from other countries. It inspired us to think more about the experiences of writers from other countries, particularly POC authors.

In thinking about these topics, I came across a compilation of essays called Letters to a Writer of Color in a small bookstore on the Upper West Side. When I saw that Ingrid Rojas Contreras, author of Fruit of the Drunken Tree (our second book of the season) was a contributor, I had to buy it.

In the introduction to the book, the editors Deepa Anappara and Taymour Soomro, both South Asian writers, reflect on their time in Western university creative writing programs, where their writing was viewed as foreign to their mostly white classmates and professors. They dissect commonly taught components of the craft, offering alternatives to the Western teachings, and unique perspectives on writing. This interview with Anappara and Soomro highlights some of these themes, and what they were trying to capture in the essay collection.

“On Trauma,” one of the essays in this collection, is written by Ingrid Rojas Contreras. She candidly reflects on how POC works of literature are often works of suffering, and muses:

Was the determination to write about [my suffering] born of me, or was it born from the gaze latent in the environment I moved in, which continually asked the story of me?…What did it mean that the story I wanted to write was also the story that was most often demanded of me?

Through this essay, she touches on important considerations for trauma narratives - how do we tell these stories? Who gets to tell them? What does it mean that most of the POC narratives we have are narratives of trauma?

Her essay is thoughtful, kind, and insightful, and I can’t wait to read the other essays in this collection.

Disability in Popular Culture and Writing

While reading our Season 2 books, we couldn’t help but notice that villainy was often tied to certain physical traits. Blindness and chronic pain, both forms of disability, feature in these books, and both are tied to villains or antagonists.

Ascribing morality to illness and disease is as old a phenomenon as illness itself. In medical school, I led a course called “Literature and Medicine.” One of the key texts that I still reflect on from this course is Susan Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor.

In Illness as Metaphor, Sontag describes how diseases have, throughout history, been seen as representations of a morally defective character. Drawing examples from novels, essays, poems, and medical writings, she describes how the diagnosis of tuberculosis was romanticized in the 19th century, and seen as an illness of passion.

As we moved into the 20th century, and medical advancements reduced the toll of TB, the cultural consciousness shifted towards cancer, a disease that became representative of shame, repression, and defeat. She describes how military metaphors, and terms like “battle” and “fight” exacerbate feelings of fear and guilt for individuals suffering from the illness.

Illnesses have always been used as metaphors to enliven charges that a society was corrupt or unjust. - Susan Sontag

Sontag’s central argument is that the metaphors we use, in our writing, in our words, and in popular culture, cause harm in the way we see others. Physical illnesses and conditions are often seen through a lens of moral judgment.

As we saw in some of our Season 2 books, this trope is not limited to the 19th and 20th centuries - unfortunately, we have carried this illness metaphor with us into the 21st century.

If you are interested in reflecting further on the way we moralize others through our views of illness and disease, and how these themes are treated in literature, in addition to Sontag’s Illness as Metaphor, I recommend Virginia Woolf’s essay On Being Ill, in which she argues that illness is a worthy topic for great works of poetry and fiction, just as love, war, and death are.

Books from Other Countries and POC that Aren’t about Trauma

This past season, nearly all the books we read focused on traumatic experiences that the characters live through. We realized that we have been exposed to so few books from other countries that are about average people living average lives. Promoted books from Asia and Africa highlight colonialism and independence wars; those from South America highlight political violence; and the books by Black authors that are celebrated usually focus on slavery or racism. And nearly every book by a POC author revolves around themes of immigration, exclusion, and discrimination.

In many cases, we know it can be impossible to separate these struggles from a person’s lived experience. And while these stories are incredibly important to read and learn about, it seems that POC authors in the West are afforded none of the freedom that white authors get with regards to subject matter. A brief look at recent award nominees and winners demonstrates this point - white authors get to tell stories like The Overstory, an intricate portrait of humanity’s relationship with nature, or Gilead, an introspective narrative about faith and forgiveness.

Meanwhile, award-winning books by authors of color have included The Seven Moons of Maali Almeida, about the gruesome murders during the Sri Lankan civil war, or Beloved, a tragic tale of an escaped slave living in post-Civil war America.

POC characters don’t get to be introspective, because the (Western) world wants to read about the violence and trauma they experience.

There are exceptions, you might say. In this day and age, we see better representation of POC characters, LGBTQ experiences, and foreign perspectives in romance novels, mysteries, YA literature - and that is wonderful. But. The literary genre has been elevated to a different plane, a more “serious” type of writing - and within this sphere, the POC novels that are celebrated are works of suffering.

Where are the coming-of-age stories with sharp social commentary, like Normal People by Sally Rooney or Elena Ferrante’s My Brilliant Friend? Where are the interpersonal dramas of Lauren Groff’s Fates and Furies? Where are the imaginative worlds of Susanna Clarke’s Piranesi and Phillip Pullman’s The Golden Compass?

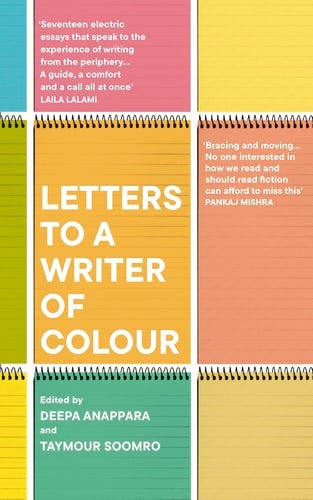

After hours of thought and research, I compiled this list of books from other countries that don’t center on war and trauma - some are books I’ve read and loved, while others are titles I’m excited to dig into.

The Museum of Innocence by Orhan Pamuk: in Istanbul in the 1970s and 80s, Kemal, a wealthy man, is about to become engaged to Sibel, the daughter of a prominent family, when he falls in love with Fusun, a poor, distant relative - their love story persists for decades, filled with loss and hope. The story is beautifully written, and I thoroughly enjoyed getting into the mind of the protagonist (who at times can be unlikeable). What I loved most about this book was Pamuk’s descriptions of Istanbul, a city that almost becomes a character in the story - straddling the East and West, the traditional and modern, and glittering with history, it is the perfect setting for the maelstrom of emotions the characters experience. If you loved Anna Karenina, you might like this book. If you didn’t like Anna Karenina - you still might like it.

The Makioka Sisters by Jun'ichirō Tanizaki: I just started reading this book about four aristocratic sisters in mid-century Japan. The eldest, Tsuroku, clings to the prestige of her family name, while Sachiko is more concerned with securing the futures of their younger sisters. The still unmarried Yukiko struggles to find a husband, whereas the youngest, Taeko, is rebellious, mired in romantic scandals. This book is filled with details about family life, disappearing customs, and the loving yet complicated relationship of sisterhood. So far I am enjoying the relaxed pacing, and getting to spend time with these characters. Reading this book feels like a grown-up version of Little Women.

The Twentieth Wife by Indu Sundaresan: in 1577, a girl named Mehrunnisa was born in what is now Afghanistan, and grew up to become Nur Jahan, one of the most famous and powerful empresses in India. Some would argue that historical fiction is an entity separate from literary fiction - so I know I’m cheating by including this book in this list, but the language is so beautiful and the themes are so universal that I’d argue that this historical fiction is also literary fiction. The first in a trilogy, this book introduces the love story of Mehrunnisa and Salim (Nur Jahan and Jahangir), gives light to the landscape of the Mughal Empire in the 16th and 17th centuries, and describes the power struggles that women have faced throughout history. I absolutely loved this book when I first read it many years ago - talking about it again is making me want to pick it up for a re-read.

Our Riches by Kaouether Adimi: translated from the original French, this small title is not only a delightful ode to books and bookshops, but it also chronicles the culture and history of Algeria in the 20th century. There are two parallel timelines: one of Edmond Charlot, a titan in the French literary world who first published the works of Albert Camus and Antoine de Saint Exupery, and opened a bookstore called Les Vraies Richesses. The other, set in modern-day Algiers, follows a young man, Ryad, who is hired to clear out Les Vraies Richesses to make room for a bakery. This book sounds like a sweet homage to books, literature, and stories, and I can’t wait to read it.

Doña Barbara by Rómulo Gallegos: this is a tale of two cousins fighting for control over an estate ranch in Venezuela. Doña Barbara, powerful and beautiful, has earned a reputation for being a witch whose strong personality fits in perfectly with the wild landscape of the Ilano (prairie). When Santos Luzardo returns to reclaim his inheritance, the ensuing battle becomes one of wits, physical prowess, and of the souls. This book, containing elements, of adventure, fantasy, and drama, has been cited as an early example of magical realism. The fact that the introduction to a new edition was written by Larry McMurtry makes me want to read the book that much more.

If you have recommendations for books from other countries, please share them with us!

— Shruti

We will be going on break from the podcast for the next month, but you can still count on regular newsletters from us.

We hope you had a wonderful holiday season, and happy new year!

Hi! I’m so happy I learned about this Substack from Chelsey Feder’s newsletter from today and was eve more delighted to read this post, which resonated with me :) thanks for all the Lit fic recs--just my jam!